Earlier this week Mike Stewart (@knowpainmike) ran a @physiotalk Tweet Chat on the hidden influence of metaphor in physiotherapy (see here, and Mike’s excellent review of the Tweet Chat here). It inspired me to think about the role metaphors play in learning.

Earlier this week Mike Stewart (@knowpainmike) ran a @physiotalk Tweet Chat on the hidden influence of metaphor in physiotherapy (see here, and Mike’s excellent review of the Tweet Chat here). It inspired me to think about the role metaphors play in learning.

If you follow this blog regularly, you will have heard the name Gilles Deleuze. If you haven’t heard this name though, it might pay to do a bit of web trawling, because some of his ideas are pretty astonishing. There have been some startling thinkers emerge from Europe over the last 100 years – Heidegger, Foucault, Sartre, Derrida, Adorno, etc. – but, for pure inventiveness, Deleuze takes the biscuit. (One tip though…I would not go to Amazon and buy one of Deleuze’s books on the basis of this recommendation. His writing is impenetrable if you don’t know what to expect and you haven’t done your homework. Don’t say you haven’t been warned!)

One of Deleuze’s revolutionary ideas concerns rhizomatics. Deleuze believes that thinking is misunderstood when we use tree metaphors to explain it. All too often, Deleuze says, we refer to its roots firmly grounded in the terra firma of reason and science, it’s branches of knowledge, all leading to the juicy fruit at the tip of each branch. Deleuze calls this kind of thinking ‘arborescent’ (meaning ‘tree-like’), and argues that thinking and learning is not really like that. While it might be part of the Enlightenment fantasy to see knowledge take such linear forms, it rarely represents reality.

Take education in health care, for example. An arborescent metaphor of learning would see graduate students as the ripe fruit at the tip of the branch. They are the product of many years of growth and maturation. They are separate from other fruit (autonomous thinkers), but they have shared some similar branches of knowledge. All of the fruit on this side of the tree has matured into physiotherapists, whose trunk was distinct from those who went off to become doctors, or nurses, or radiographers. But they all shared a common stem (basic sciences) whose roots are grounded in the firm soil of reason and logic. Learning is a process of maturation, and when the fruit has served its purpose, it falls to the ground to replenish the next generation’s learning.

Arborescent ideas have been very powerful in our recent history. Look, for example, at this review of the beautiful ‘Book of Trees’ here to see how pervasive arborescent metaphors have been in our cultural history. They have governed how we think we learn, how we like to organise ourselves and our time, how we think about problem solving. But it is also, after all, only a metaphor; a simpler way of understanding something complicated. We have been learning to think like this since we were little green shoots in the ground. But it isn’t the only way to think, and it might not even be the best way today.

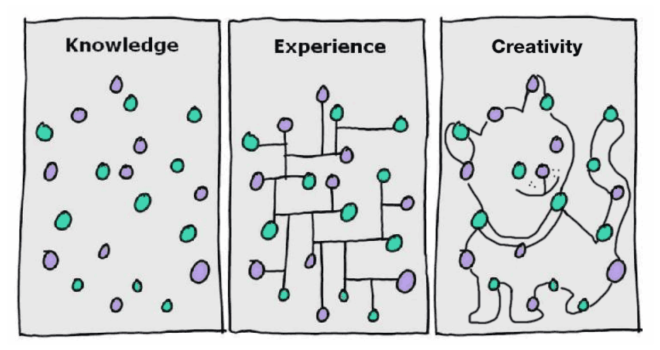

One of Steve Wheeler’s recent blogposts looked at the need for creativity in learning and featured this lovely image:

In the post, Steve asked ‘What happens when you remove restraints from learning, and allow students to discover for themselves? What happens when students are given problems to solve rather than solutions to apply? What happens when students are given blank canvases, digital cameras, an open space? Often, the result is some form of creativity.’

I’ve talked before about the importance of opening space for uncertainty and unpredictability with our students before, but of course this runs counter to what you’re supposed to do with arborescent thinking. There is no room for deviation when you’re trying to produce fruit for export! Everything has to follow along straight lines so that no time or energy is wasted. Henry Ford would be proud of the efficient way we now produce health graduates fit for practice. But is it good for the patient?

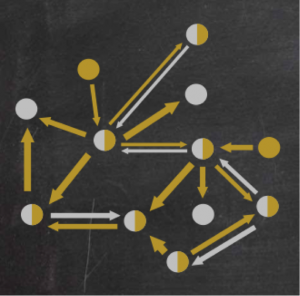

The other day I posted about Open Badges and the way they are challenging the right of authorities like universities and professional bodies to define what the fruit at the end of the branch looks like. Sites like Crowducate are promoting alternatives to linear, arborescent education and using rhizomatic metaphors like this to do it (see here).

21st century learning is looking increasingly like it will subvert the idea of linear, arborescent thinking, creating learners who are far more flexible and adaptive to a less-than-certain future. Physiotherapists need to get their heads around this and find better metaphors for learning than just an age-old reliance on trees.

This is where Deleuze may come in.

Deleuze said ‘We’re tired of trees. We should stop believing in trees, roots, and radicles. They’ve made us suffer too much. All of arborescent culture is founded on them, from biology to linguistics’ (Deleuze & Guattari, 1987 p.15). Deleuze proposed an alternative way of thinking that was, what he called, rhizomatic.

Learning and knowledge, he said, was much more messy. Ideas actually had no beginning or end, and you were always in the middle – in one form or another. In fact there are multiple ‘middles’ – ever point is just another ‘middle.’

Dave Holmes and Denise Gastaldo have written that unlike trees ‘…the rhizome is open at both ends. It has no central or governing structure; it has neither beginning nor end. As a rhizome has no centre, it spreads continuously without beginning or ending and basically exists in a constant state of play. It does not conform to a unidirectional or linear reasoning’ (Holmes and Gastaldo, 2004, p.261). (The Holmes and Gastaldo paper actually offers a really useful introduction to the whole idea of rhizomatics and is well worth reading).

The point is that the metaphor of the rhizome might provide a more useful way to think about the future of learning, and offer something more relevant to the way learning is emerging as a distributive, community activity in the 21st century. It might be time to turn away from trees and focus on the fungi instead.

References

Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1987). A thousand plateaus — capitalism and schizophrenia. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Holmes, D., & Gastaldo, D. (2004). Rhizomatic thought in nursing: An alternative path for the development of the discipline. Nursing Philosophy, 5, 258-267.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.