For some years now, I’ve been researching physiotherapy history. Sometimes doing this kind of work throws up surprising and poignant reminders of how much has changed, and also sometimes how little.

A few weeks ago, I found an old newspaper article from The Otago Daily Times from 1957. The article had been given to me by an a retired physio who knew I was collating material for an interactive website we were creating to celebrate the centenary of physiotherapy in New Zealand (link).

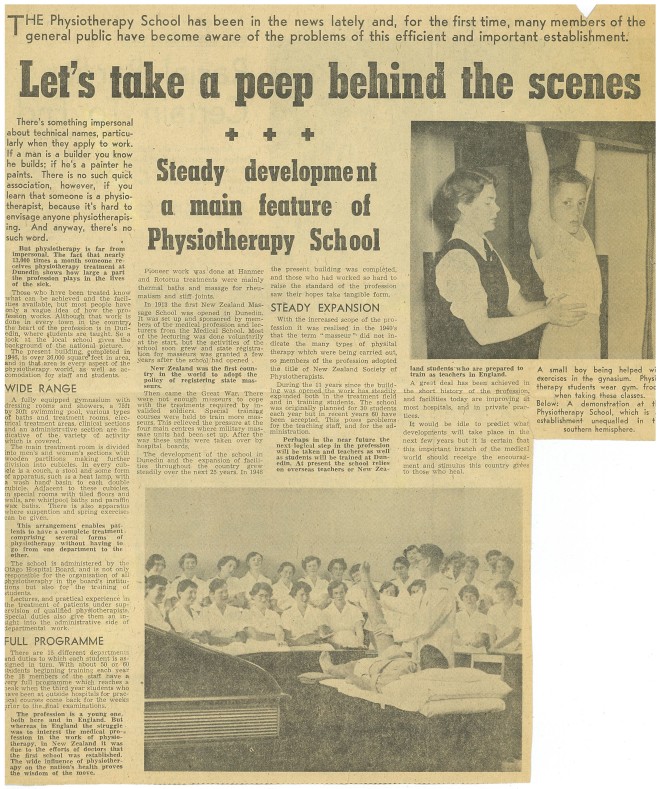

The article was a simple piece about the School of Physiotherapy. At the time this was the only physiotherapy school in New Zealand and the article talked about how the school ran, what the students did and how the school fitted into the town’s established university.

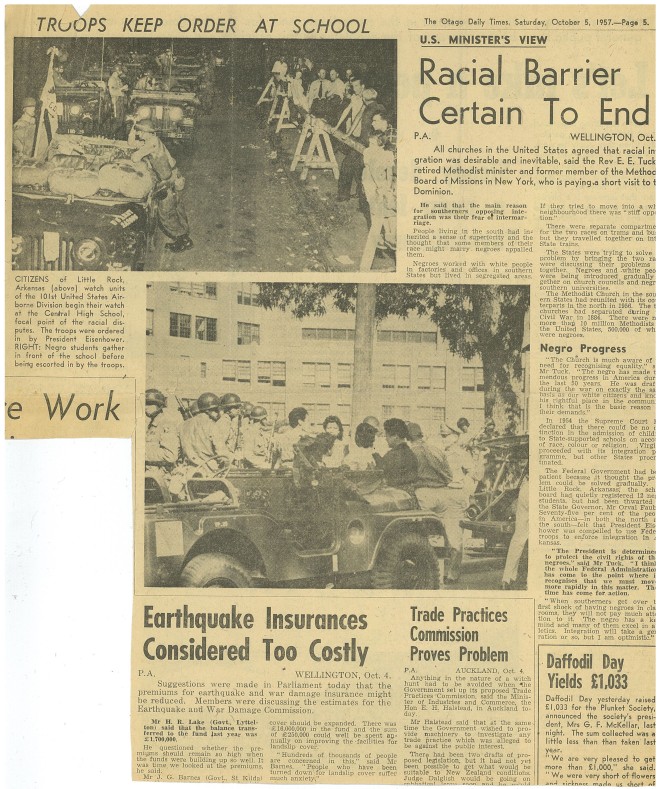

For some reason I turned the newspaper article over. At first I didn’t realise what I was looking at, but then as I started to read I realised that the newspaper was reporting on a major event in US history.

Little Rock is synonymous with black civil rights in America. Three years earlier, the US Supreme Court had called for all high schools to desegregate, but school officials in Little Rock, Arkansas defied the order. Blackpast takes up the story:

School district officials created a system in which black students interested in attending white only schools were put through a series of rigorous interviews to determine whether they were suited for admission. School officials interviewed approximately eighty black students for Central High School, the largest school in the city. Only nine were chosen, Melba Patillo Beals, Elizabeth Eckford, Ernest Green, Gloria Ray Karlmark, Carlotta Walls Lanier, Terrance Roberts, Jefferson Thomas, Minnijean Brown Trickey, and Thelma Mothershed Wair. They would later become known around the world as the “Little Rock Nine.”

Although skeptical about integrating a former white-only institution, the nine students arrived at Central High School on September 3, 1957 looking forward to a successful academic year. Instead they were greeted by an angry mob of white students, parents, and citizens determined to stop integration. In addition to facing physical threats, screams, and racial slurs from the crowd, Arkansas Governor Orval M. Faubus intervened, ordering the Arkansas National Guard to keep the nine African American students from entering the school. Faced with no other choice, the “Little Rock Nine” gave up their attempt to attend Central High School which soon became the center of a national debate about civil rights, racial discrimination and States’s rights.

On September 20, 1957, Federal Judge Ronald Davies ordered Governor Faubus to remove the National Guard from the Central High School’s entrance and to allow integration to take its course in Little Rock. When Faubus defied the court order, President Dwight Eisenhower dispatched nearly 1,000 paratroopers and federalized the 10,000 Arkansas National Guard troops who were to ensure that the school would be open to the nine students. On September 23, 1957, the “Little Rock Nine” returned to Central High School where they were enrolled. Units of the United States Army remained at the school for the rest of the academic year to guarantee their safety.

Sources:

Elizabeth Jacoway, Turn Away Thy Son: Little Rock, The Crisis That Shocked The Nation (New York: The Free Press, 2007); Mark Carnes and John A. Garraty, The American Nation: A History of the United States Since 1865 (New York: Longman, 2003).

It is sometimes tempting to think that we are far more sophisticated and enlightened than our forebears, but studying history has always taught me otherwise. Given the ongoing police shootings of young black men across America, we would be wise to remember Franklin D. Roosevelt, who said “The test of our progress is not whether we add more to the abundance of those who have much it is whether we provide enough for those who have little.”

That seems to me to be a good test of physiotherapy practice, never mind civil rights.

What I think this highlights is not only providing for those with little, but more importantly facilitating access.

I have always been surprised by how very few people I have met in my working career (colleagues and ‘patients’) who have significant hearing and visual impairments or who are wheelchair users. It makes me question their access to and within: in a health ‘system’, the accessibility or place of the first point of contact for onward referral or employment impacts on the diversity and inclusiveness of the whole system. In this example, embracing the little rock nine meant a greater access throughout society with the USA eventually having a black president. So little acorns and great oak trees spring to mind.

Thanks Dave, this not only helps consider local access but also the powerful, expansive effect little changes can have on society as a whole.