Survivor, a short poem by Roger McGough:

Everyday,

I think about dying.

About disease, starvation,

violence, terrorism, war,

the end of the world.

It helps

keep my mind off things.

That poem always makes me smile. I used to have it on my office wall for the times when I thought I was taking myself too seriously. I was reminded of it after last week’s rather heavy blogposts about physiotherapy and sex. So I thought I’d post about something a bit more lighthearted today. In the spirit of Roger McGough then, this post is about video violence, simulated injury and death.

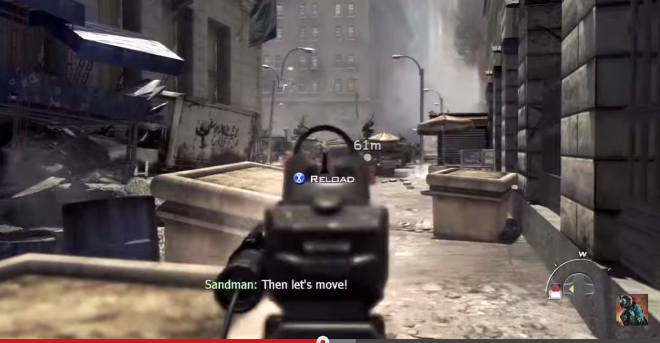

For some time now I’ve been pondering why it is that there are no physiotherapists working – and I mean actually employed – in first-person video games: games like Call of Duty, Halo, Far Cry or Half life? (If you have absolutely no idea about these games, you can watch video recordings of game play on Youtube – this link is of a live player showing you their game play, for example – but they basically involve gamers taking on the persona of an in-game character and shooting their way through billions of challenges until everyone else is dead or they’ve evolved so much that they’ve become bored by their own invincibility.)

Let me be clear, I don’t play these games, but I know enough about them to understand the basic idea. Your player develops skills throughout the game based on live challenges. The games are meant to be so immersive that you almost believe you are in the fantasy world, and having seen a couple of these games played, you have to admire the skill of the designers because the worlds are impressively realistic. But here’s the rub…

The games are designed to be a simulation of real life. For instance, the games ‘physics’ have to be realistic. They have to feel real, so that when your character runs, it has to look and feel like you are running. Water has to flow like water and rocks have to look heavy to lift. Things you throw have to fly right and bigger guns have to sound more impressive than pea-shooters. They have to be a simulation of the real world, and the lengths that game designers go to to simulate these in-game physical properties of matter border on the obsessive. And yet, at the same time, the games all perpetuate the most ridiculous deception, and everybody who plays knows it and accepts it.

The games are designed to be a simulation of real life. For instance, the games ‘physics’ have to be realistic. They have to feel real, so that when your character runs, it has to look and feel like you are running. Water has to flow like water and rocks have to look heavy to lift. Things you throw have to fly right and bigger guns have to sound more impressive than pea-shooters. They have to be a simulation of the real world, and the lengths that game designers go to to simulate these in-game physical properties of matter border on the obsessive. And yet, at the same time, the games all perpetuate the most ridiculous deception, and everybody who plays knows it and accepts it.

Everything is real until the point comes where the player gets injured, or worst still, dies. Then the game allows the player to magically regenerate. They may have to find a medical chest or suffer the inconvenience of a slight game delay, but the penalty is little more than waiting a few seconds or a slight detour on their journey.

This seems a bit odd to me. On the one hand, gamers demand that the gameplay is as authentic and immersive as possible, right up to the point where they get injured. Then they just want a convenient quick fix and a sloppy unreal world is allowed to intervene so that their gameplay is not disrupted.

If a player jumps out of a 2nd floor window or has their arm chopped off in a fight with a bulbasaur (you can tell I’m not a pro gamer!), shouldn’t they have to stand down from the game for two months while they recover? Shouldn’t they have to pay for their surgery and rehabilitation? Shouldn’t a physiotherapists be employed somewhere in the game to make sure they followed the right programme of exercises and didn’t lose their aerobic fitness? And what happens if their surgical repair gets infected?

If a player jumps out of a 2nd floor window or has their arm chopped off in a fight with a bulbasaur (you can tell I’m not a pro gamer!), shouldn’t they have to stand down from the game for two months while they recover? Shouldn’t they have to pay for their surgery and rehabilitation? Shouldn’t a physiotherapists be employed somewhere in the game to make sure they followed the right programme of exercises and didn’t lose their aerobic fitness? And what happens if their surgical repair gets infected?

Why are there no physiotherapists working inside video games like Call of Duty?

There are, of course, a few quite serious philosophical questions underlying this problem (not least how gamers are experiencing their embodied selves in virtual space). But more importantly, for us at least, is a question about the ways physiotherapy may change in the future if people who develop very different view of the limits of their bodies. Virtual reality games are only one expression of the many possibilities promised by future genetic therapies, robotics, reconstructive surgeries and pharmacological interventions. It’s not inconceivable that we are on the threshold of radically new ‘cyborg’ bodies where new technologies may make a lot of our present modes of rehabilitation obsolete.

So why couldn’t a physiotherapist make a living in an entirely virtual world? Do we actually need a physical body in front of us to practice? Clearly not. There are businesses being set up already where the therapist is remote to the client/patient. So why not online? Do we really still believe that embodied reality is corporeal?

Hi David. Interesting idea…the notion of injury to virtual bodies. What does it mean for a virtual self to be damaged? Have you come across the work of Deborah Lupton (https://simplysociology.wordpress.com/). I’m not sure how closely her work might converge with your post but she writes about our relationship with our digital selves.

On a partially-related note: have you seen this: http://www.ted.com/talks/cosmin_mihaiu_physical_therapy_is_boring_play_a_game_instead?

thanks Dave – am enjoying your recent blogposts on bodies/embodiment & physiotherapy. This post on virtual/corporeal realities took me back to my visit to ‘Superhuman’ at the Wellcome Collection back in 2012 http://wellcomecollection.org/whats-on/exhibitions/superhuman This fascinating exhibition highlighted the tensions around the practices & ethics of bodily enhancement (eg prosthetic limbs & performance enhancing clothing, surgical sculpting/implantation & digitally enhanced realities) & left me with a heap of questions about the bodies we produce/experience (& those we silence) through our engagement with techniques & technologies as physiotherapists. Would be great to have some discussion about the ethics/politics of working with ‘superhuman’ bodies & how those experiences are shaping our understanding of bodies & bodily practices.

Hi Gwyn

I managed to get a copy of the exhibition booklet for Superhuman from my mom. Sadly I couldn’t get over to see it. I’ve spent quite a bit of time at the Wellcome researching physio history. It’s one of my happy places :0) The Peyton and Byrne cafe on the ground floor has nothing to do with it! Thanks for the link to the exhibition…I hadn’t seen that. The question of working with cyborg/post-human bodies is a subject I’d really like us to get into…we’ve made it the focus of our brief meeting at the ISIH conference in Mallorca. We’ll keep notes and disseminate them through the network afterwards.

Hi Michael

I know Deborah’s work very well. I’ve followed her for a long time. She’s at the University of Canberra and I got into a rather awkward fan-boy stalking kind of thing with her a while back while I was visiting the campus. (A story for another day!)

And yes, I have seen the TED talk (I think I Tweeted about it recently). Interestingly, I think the talk showed up the limits of simulation rather than it’s strengths and made me think how we have to change our mindset about the possibilities for post-human rehabilitation if we’re really going to do something interesting. What did you think?

Hi David

I agree, I don’t think there’s a lot interesting about video games as part of traditional conceptions of therapy. It’s just more of the same, with added technology. People have been using Nintendo Wii balance boards for patients with neurological dysfunction for almost a decade, so this is not terribly exciting (IMO).

I did spend a little bit of time as a co-researcher on a posthumanism and social justice research project, along with Rosi Braidotti, who was one of the primary researchers. But I had to step down after taking on some other work, so have had only a brief foray into the field.

I’m interested in the idea of posthumanist thought but my interest is more technical than theoretical i.e. more Ray Kurzweil than Braidotti. I do spend time thinking about how physiotherapy will need to change when software, hardware and “wetware” are more closely integrated. For example, what does it mean for the profession when robotic prosthetics are being hooked up directly to the nervous system? Are we teaching our students how to work with exoskeletons that augment function? What about augmented reality overlaid onto the retina? None of these are science fiction and are currently being trialled, yet I can only mention them in passing to my students because they don’t form part of the curriculum as required by our professional body.

Reblogged this on William Chasterson.